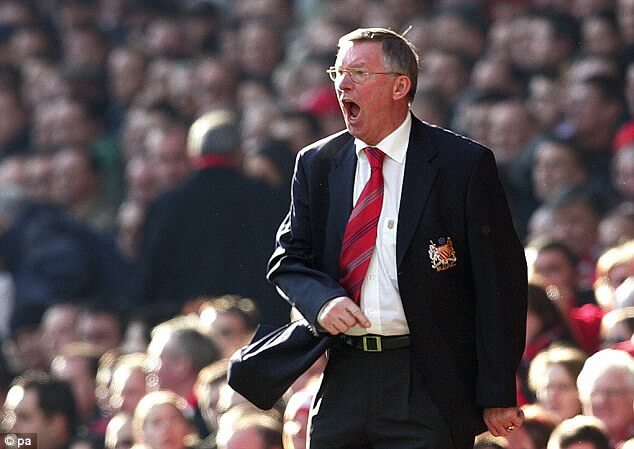

Sir Alex Ferguson in customary pose, yelling at his players

Sir Alex Ferguson, one of the greatest football coaches, was famous for “giving his players the hairdryer treatment”, ie yelling at them.

Today a repost of a wonderful interview this week by Kieran Shannon of the Irish Examiner of Wayne Goldsmith.

I have been focussed for many years on the overlaps between coaching sports and coaching individuals and business. I am privileged to count as a dear friend one of the swimming worlds all-time great coaches, Ian Armiger (who shared this article me too).

I’ve learned as much or more from top sports coaches about human behaviour as any business or leadership thinker, speaker, consultant or coach.

So many nuggets in this powerful article, but one that truly stands out from me and is so, so relevant to all forms of coaching, mentoring, management, leadership:

“As a coach, start connecting with the players, even if they’re as young as six. Don’t tell and yell — ask.” ~ Wayne Goldsmith

He then goes on to explain that most coaches spend 70% of their time commentating and otherwise being unconstructive, only 30% being of true value. Oh, and that a calm coach is far more valuable than one who yells.

As for Sir Alex Ferguson, as I wrote about in: “Ferguson and Cantona – Vulnerability and Strength“, there was much more to Sir Alex than the “hairdryer”.

Enjoy the article and I hope you take at least two or three things from it you can apply yourself in your life, work, family. If you are a sports coach, perhaps you too can learn specifics from Wayne Goldsmith too.

Oh, and as to family, the final part of the article talks about swim parents not allowing their children to take self-responsibility for what they need and need to do. How often do we do that as leaders and managers too? Allow your people, your kids, your community to step up rather than you jump in to fix things. You may be powerfully amazed at what happens.

So, enjoy the article, the bold type parts are my contributions to highlight certain sections. I give you just one here:

“Creativity comes from difference. Being able to see different connections. Constantly rejecting what is and looking at what could be.”

I hope you find more for yourself too.

Fortnite is not sport’s enemy — outdated coaching is

By Kieran Shannon

The world-leading coach educator Wayne Goldsmith has worked with everyone from the All Blacks to the US Olympic swimming team of Phelps and Lochte and the top sides in the AFL, but his driving passion as he visits Ireland is that parents and coaches at the grassroots help keep kids playing and enjoying sport.

Wayne Goldsmith shares both a dream and a nightmare he has for Irish sport.

Although he’s been a consultant to the All Blacks and the Wallabies over the years, he adapts a story he told as the keynote speaker at the 2017 World in Union International Rugby Conference in New Zealand while the British and Irish Lions were in town.

“Imagine Ireland win the World Cup — and let’s hope they do. And three little boys and girls run down to their local club, all excited. ‘We want to try and play rugby!’

“And there at the field to meet them is this old guy, Jack. Jack has been helping out at the club for 30 years. A wonderful old guy. Played the game himself. Served as club chairman. A member for life. Has all the right intentions.

“But then when the kids arrive, Jack tells them, ‘Right, we’ll start with a four-lap warmup.’ Because that’s how he’s always coached and probably how he was coached himself.

“Then when the kids come back, he’ll tell them, ‘Right, now we’re going to do some drills. Into a straight line…’ Because he has all these drills he saw and learned at some coaching course years ago. Passing drills. Breakdown drills. He has more drills than a hardware store.

“Then, just before they go home, he says, ‘Okay, we’ll play a game for five minutes.’ The one thing they went to see him for, Jack only gives them right at the end.

And that what is killing sport.

Because, as he’s found in his work as a coach educator, there are a lot of Jacks out there. All across the world, across all the sports. And everywhere, in every sport, it’s the same: The number of kids who fall out of playing competitive sport is falling drastically.

In his hometown of Sydney, there’s 50% fewer kids swimming and playing rugby league than there were 20 years ago.

Modifying the rules and the games isn’t enough to stem the haemorrhaging. Coaching — coaches — need to modify. Adapt.

“The experience we’re giving kids is generally out of touch with what they want. The default setting of the majority of coaches around the world still is to be predominantly physically-based and repetition-based, telling kids to do laps and yell times. That’s not coaching, connecting, inspiring.

“My strong belief is that the solution to turning around the falling numbers playing competitive sport is to change coaching. To make it more relationship-based and experience-based.”

He has an interesting take on the phenomenal appeal of the video game, Fortnite. Just the other week, a coach he was talking to in the US bemoaned the popularity and appeal of the video game. How engaged kids were with it. The instant gratification it provided. Goldsmith didn’t so much empathise with him as advise him to empathise more with those hooked kids.

“I said, ‘Well, maybe you’ve to come up with some form of Fortnite yourself. A way of coaching that is engaging, inspiring, allowing them to connect with others.’ If you’re waiting for kids to change and go back to the way things used to be, you’re deluded. Life doesn’t go backwards. And the issue isn’t that kids have changed. They haven’t. The problem is we haven’t changed. We’ve to come up with ways to find it interesting and exciting for them to want to work hard and get better at sport.

Fortnite has no drills. The game is their teacher. A friend of mine in the Australian football federation was working with some coaches recently.

“He asked them what a typical session would be like. They said, ‘Well, we warm up, do a drill…’ And he said, ‘Stop right there! I want you to do the opposite of that!’ I laughed. But as he said, ‘The kids are not there to do drills or to do speedwork. They’re there to have fun and play the game. And if you don’t give them that, eventually it’ll add up and they’ll stop coming.’

“Coaches say to me that they have to build the aerobic base when they’re young but I’ll say, ‘Physiologically, that might be right, but the only athlete who can’t get better is the one that isn’t there.’

“The dropout rates tell us — the way we’re doing it is wrong. We’ve got it wrong. The kids are not wrong.

“Things like aerobic fitness or core stability — those things shouldn’t really matter until the kids hit 14, 15 and are deeply involved in the sport and committed to excellence. Before that, it’s about enjoyment, experience, movement.

“As a coach, start connecting with the players, even if they’re as young as six. Don’t tell and yell — ask. If we’re playing football, I’ll often say to kids, ‘Okay, guys, how can we make this faster? Can anyone come up with a game where we only use our left foot?’ It’s about their experience of the game. Not us imposing our experiences and motivation onto the kids.”

Any coach taking in a workshop of his on his whirlwind tour around Ireland over the next couple of weeks can take comfort in the fact Goldsmith himself knows how humbling and challenging it can be to learn and to teach.

Coach educator Wayne Goldsmith only discovered at the age of 49 that he was dyslexic with a form of ADHD, but he points out: ‘One of the great things that’s happened recently in society is that if you’ve got kids with different learning styles or on the autism spectrum, they can be better accommodated.’

By his own admission, he was a “terrible” high school student. His final test score was 121 out of 500. He only discovered why eight years ago, at 49 years of age, after reading a Harry Potter book to his daughter. “Dad, why are you changing the words on the page?”

Her comment irked him, so much so he mentioned it to his wife Helen that night, but she came to a similar conclusion when he started reading her bedside magazine. A few months later he was diagnosed as dyslexic with a form of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

I broke down crying and said to my wife, ‘I want my life back.’ A lot of things I had failed

at, I could never understand why.

For a decade after leaving school he held down menial-enough jobs, in storehouses, packing goods. He worked in a bank for a short while but only a short while; all those systems and all that routine wasn’t for him.

Then when he was 28, he bumped into an old school friend who commented upon how much weight he’d put on from when they used to play rugby and football together. Their conversation triggered Goldsmith into taking up running and repeating his high school exams to enrol in a sports science course at the University of Canberra, right next to the world-leading Australian Institute of Sport.

Looking back, he feels blessed how understanding his lecturers were, though it helped he was around the same age as most of them. He was failing in physiology but his lecturer suggested he submit his assignments a week early and he’d give some feedback before Goldsmith would complete them.

The same lecturer also recommended the anatomy and physiology colouring book, ideal for people who learned less by rote but by images. And so he’d pencil in his atrium in one colour, and the aorta in another.

He’d walk down to the Institute of Sport which had a huge video and audio library, sit into a booth, and plop in and listen to these old cassettes of lectures on physiology, so often, they just sank into his head. It was all about what he often tells athletes and coaches now: Find a way. Be creative.

“Almost everyone we admire, from Plato to Picasso to Steve Jobs, the thing that made them great was that they were unique. One of the great things that’s happened recently in society is that if you’ve got kids with different learning styles or on the autism spectrum, they can be better accommodated. A friend of mine is an animator and she jokes that if it wasn’t for dyslexia or ADHD or autism or Asperger’s, she’d have no students in her class. Creativity comes from difference. Being able to see different connections. Constantly rejecting what is and looking at what could be.

“When I’m listening to or watching a client, my brain is immediately coming up with 20 possible directions we could go in. ‘I wonder could we change this.’ I never really understood why until I read that Harry Potter book. So now I look at my [conditions] as a great advantage, though it often drives my wife mad..

“The business we’re in, there’s a lot of copying. ‘Oh, the All Blacks are doing this, so we should do this too.’ But what I’ve learned in the high-performance area is this: Copying kills. There is a reason I’ve survived. I don’t copy. At least not gimmicks. I try to come up with new directions. It doesn’t always work but eventually we tend to find a way. And if you think about it, almost all the great coaches have an artistic, creative side.”

He’s been fortunate to work with more than his share of them. In 1993, the same year Australia won the bid to host the 2000 Olympics, Swimming Australia created two new full-time positions: Goldsmith as its manager of sport science and medicine, and a Bill Sweetenham as its national youth coach.

Goldsmith compares travelling with Sweetenham to travelling with a cat – sometimes very pleasant, sometimes challenging. Together with others they’d assist the likes of Ian Thorpe reaching the podium in Sydney but what impresses Goldsmith most is how Sweetenham continues to evolve in his current role with Argentinian swimming, a year shy of his 70th birthday.

“Bill is very different to even 10 years ago. He’s still got that relentless, uncompromising attitude to excellence but he’s very much adopted this whole athlete connection partnership model. I saw him in action last year. The old Bill would have told the athletes war stories. Instead he said to an athlete, ‘If you had to rate your effort out of 10 in this session so far, what would you give yourself?’ ‘Six.’ ‘Okay, what do you think you can do to make it an eight or a nine?’ The athlete then came up with a couple of suggestions and Bill said, ‘Excellent decision.’ And off the athlete went.

“Bill helped give them a plan, their own plan. You can be hard and uncompromising about standards without raising your voice.

Goldsmith himself has worked extensively with US swimming, observing the likes of Michael Phelps, Ryan Lochte, and Missy Franklin and collaborating with coaches such as David Marsh. Then closer to home, he’s worked with the likes of Graham Henry and Wayne Smith and Steve Hanson in New Zealand rugby. He’d like to think they’ve learned from him but he knows for sure he learned so much from them.

Marsh once nailed for him the definition between the great athletes and the merely good: When given a choice between the easy way and the hard way, the great athlete will choose the hard way. Henry coined and lived the term Getting Better Never Stops. And Smith is someone he considers “the smartest rugby mind I’ve ever met”. Goldsmith finds that whenever he returns from New Zealand having maybe called into the Crusaders, people will often enquire as to what they’re doing, how they admire and copy them. Goldsmith barely humours them. No point in copying the All Blacks, guys, they’ve already moved on to something else. And as for values like humility and sweeping the sheds, are you sure they’re not just words and tokens from you when you say you copy them

“I often say, values have no value unless you live them, not just talk them. Because every team has those meetings at the start of the year. So my job is to ask players and coaches what a value looks like in a given circumstance. ‘Okay, you talk about respect. What does respect look like at 11pm in a bar in the middle of Dublin when you’ve had a few pints? What are you doing to bring the value to life?’ If you don’t take that step, then all you’re doing is writing nice words but wasting money.”

In recent years he’s started working more with rugby sides in his home country: The national team, like he would have previously during Eddie Jones’ tenure, as well as with the Brumbies, where former Munster forwards coach Laurie Fisher is head of the academy.

He likes how both set-ups are being creative and adaptable in their thinking. Recently Rugby Australia brought in six or seven past Wallabies coaches to discuss what rugby could look like in three, five, 10 years’ time. But he particularly prefers working with players and coaches on the training field.

“Coach education in the classroom is largely a waste of time,” he says. “I prefer now to what I call ‘shadow’ coaches. Be next to a Laurie on the field, so you can ask a coach in real-time during a water break, ‘Why did you do six of those?’ Because just like the players, that’s when they’re most receptive to learning. If a player needs to change their tackling technique, as a coach you don’t wait to the next day — you tell them right there and then. As a coach educator, it’s the same. I feel you have to be in the mix.”

As much as his beautiful mind can sometimes drive her mad, his wife Helen, a psychologist and a double-Commonwealth swimmer, works with him on certain professional projects. Right now they’re working with an AFL team to help their coaches communicate more effectively in-game. And so, Team Goldsmith video and audio record the team’s coaching box during games, and then dissected and categorised their communication.

“We’ve identified four types of talk. Venting — that’s coaches yelling and screaming at someone’s decision. Commentary — a coach essentially commentating on the game, stating the obvious. Then there’s what we call directed discussions — towards making a decision — and then there’s decision making.

“When we did it the first time, I said to the coaches, ‘Are you aware that about 70% of your in-game communication is either venting or commentating? Only 30% of it is intelligent conversation.’

“The best coaching boxes tend to be very calm. Very little venting. Little commentating as well. If you’re commentating, then you’re looking at the game like a spectator. That’s not what we’re being paid for. We’re pros. We’re being paid to make good, logical, informed decisions at the right time.

“The players are looking for the coaches to offer clear, calm decision-making. Anything that gets in the way of that — including possibly anger — needs to be eliminated.”

So he and Helen help them come up with strategies to do just that. He won’t go into it here just how and what, it’s the AFL team that are paying for such a service, not us, as much as we’d love to see him extend it to Davy Fitzgerald some time.

Over the next couple of weeks though he’ll be working with plenty of Irish coaches. On Monday he’ll be in CIT where the Cork GAA underage movement, Rebel Óg, have teamed up with the college to host an interactive workshop of his. He’ll also be teaming up with numerous swim coaches and swimmers from having linked up with our national performance director John Rudd — “an excellent coach” — over the years.

He’s especially looking forward to meeting the parents too. Help them. Challenge them. There’ll be at least one session where he’ll ask them to stand up if over the last 48 hours they’ve done any of the following: Packed their kids’ bag for training. Set the alarm. Emptied and filled their water bottle. Nine out of 10 are usually on their feet. He’d prefer if the nine of them were still seated. Athletes need to learn to be independent and accountable. Let the kid set the alarm and have the breakfast and then gently wake and remind you if you could drive them to that early morning pool session.

“Parents are acting out of love and showing care but they’re not actually helping their kid because confidence comes from knowing and knowing comes from doing. If parents are doing everything for the kid, they never learn the ‘I can’ mindset, that ‘If it’s to be, it’s up to me.’”

And then he’ll look them in the eye and ask them: Have you looked your kid in the eye and let them know they’re loved and valued for no reason other than they are your child?

Only one in 10 parents tend to put their hand up for that one, when he’s looking for a full house.

“We need parents to demonstrate unconditional love and acceptance and be that emotional rock.”

Even when that kid messes up in a game. Or tells you you’re reading Harry Potter wrong.